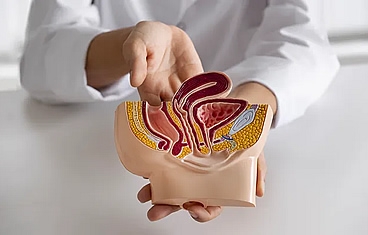

When a patient loses a significant amount of genital tissue due to trauma, burns, or infection, genital reconstruction surgery can help restore anatomy and minimize scarring. The genitals are traditionally difficult to reconstruct and often require a combination of muscle flaps, skin grafts, or even tissue expander balloons placed under the skin. Reconstruction of the urinary tract involves reconstructing the structures that store or transport urine-namely, the bladder, urethra, and ureter.

Bladder reconstruction usually involves increasing the size of the bladder with a portion of the small intestine or colon and then bringing the urine to the skin through a surgically constructed channel that can be continent (catheterizable channel/Mitrofanoff) or incontinent. When the bladder is completely removed, we can recreate a "new" bladder with small intestine (neobladder) in an orthotopic manner by reconnecting it to the native urethra or in a heterotopic manner through an abdominal conduit (ileal pouch).

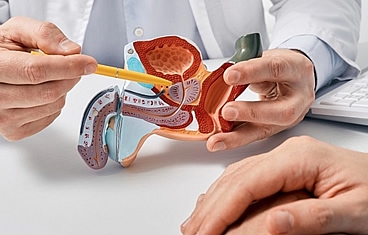

Urethral reconstruction involves a combination of skin grafts, oral mucosa grafts, and skin and muscle flaps to increase the urethral diameter so that urination can be restored to normal.

Ureteral reconstruction typically involves filling the gap of the absent or diseased ureter by replacing the ureter with an elongated bladder, a bladder tube, or a segment of the small intestine or appendix to act as a chimney to transport urine to the bladder.

Laparoscopy and robotic surgery are suitable and minimally invasive options for ureteral and bladder reconstruction and help minimize hospitalization and overall recovery time. Robotic reconstruction is an evolving and expanding field, and at iPROURO, we are committed to using the most advanced surgical techniques. We foresee that most abdominal urinary reconstructions will become less invasive over time and with our growing experience.

Reconstructive urology is an evolving field; many of the procedures we commonly perform today did not exist ten years ago. We embrace innovation and collaboration. With a reflective and open mindset, we continually strive to improve and refine our functional and cosmetic outcomes.